By David Madureira

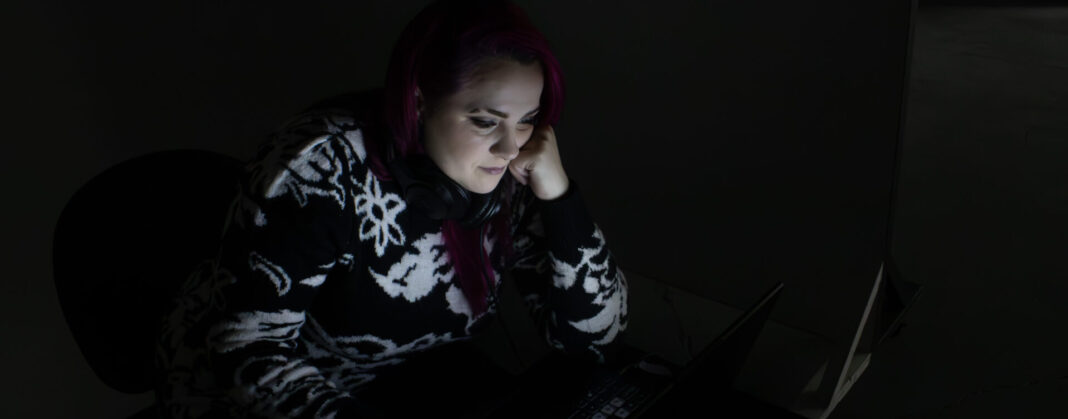

Every time Kendryx Linscott, whose pronouns are they/them, steps into their workplace and sits down to do their work, they are constantly being bombarded by the comments said by their male coworkers under their breath. They say things like “Women should go back to the kitchen.” “Women should be cleaning.” “Women are only there to be partners/girlfriends.” and the only way for them to be able to stand to work now is to put on their headphones to drown it out.

Kendryx is now Chief Marketing Officer for Esport Canada, and formerly the Chief Marketing Officer for Women In Games International and head of digital for EsportsGG and her experience in the workplace adjacent to Esports has been much of this.

“It was every day I’d walk in, put my headset on and I would just do my work, and keep my head down, and get my assignments done, and then go home and then try to decompress. And it was like looking back it was like ‘well what kind of workplace was that?” Linscott recalls.

Esports has been a very male-dominated industry since its inception, and has a lot of the problems of other typically male-dominated spaces such as the aforementioned locker room talk. But why?

To start at the very beginning, video games, like everything else, were marketed to a very specific audience in mind since they’ve been made commercially available.

“The gaming industry at large really has a long history of being promoted exclusively to men, all the way from the top to the bottom,” says Egil Trasti Rogstad, an associate professor at the University of Norway, and a sociologist who studies gaming and specifically how it relates to gender.

Video games as a whole were largely marketed as a “boy’s toy” in the late 1980s to early 1990s.

“Some researchers at least talk about a geek masculinity that is associated especially in the earlier part of gaming history, because you know, as you probably see movies from like the 80s [and] 90s, where gamers are presented as nerds. So, it isn’t like gamer masculinity has always been on top.”

In that time though, according to Egil, gaming and being a ‘gamer’ was seen as more of a ‘nerdy’ and less masculine thing to do. Video games not requiring any physical activity have led to many ‘nerd’ stereotypes to be associated with people who play games. But as video games have become more mainstream, these stereotypes have become less prevalent and more traditional businesses began to take notice.

Teams won’t add women to their rosters because they see them as distractions or bad influences.

Kendryx Linscott

Bernard Mafei, Senior Administrator of Humber College’s Esports, speaks to the rise of Esports.

“So, I will say maybe four to five years ago, there was a lot of investment in the industry, a lot of statistics arenas being sold out, like the promise of something major. And a lot of investors, they put money into teams, events, solutions, companies, because there was so much hype,” he says.

Despite Esports now being more popular, its history still affects the industry to this day.

“From the game producers themselves down to the game developers [and] designers are usually all men. Games have been promoted in a commercial sense to a male audience.”

This has resulted in gaming generally having a very male-dominated presence that visibly continues into Esports today. This homogeneity may have given way to a sort of exclusionary mindset in many men in the scene.

“Part of the toxic masculinity idea is that you know, in order to show that you’re a real man or a real gamer, yourself, you have to, like, do that. On the expense of other forms, that is like femininity, and what is seen as feminine qualities, etc.,” Mafei says.

Egil continues on this point.

“Yeah, it’s very much like a space thing, trying to guard being like the gatekeepers. So, that’s very important to some gamers, within the industry. And that’s what you also see with more like, women teams, or female teams or women tournaments, also, like the resistance towards that is sometimes they’re scared that those kinds of teams, tournaments are drawing attention, money, etc., from like the real gamers.”

Linscott has experienced this kind of mindset firsthand. They started playing a video game called Dota 2 and immersed themselves in its culture and knowledge.

“I knew the competitive scene inside and out,” they say.

But there were times when their knowledge was questioned by their colleagues.

“I would have people ask me questions about Dota and then they would turn around and be like ‘I’m going to ask your colleague over there just to verify’ Implying that they lack the knowledge,” Linscott recalls.

“I’d be like ‘but buddy over there plays CS:GO’ and they’d be like ‘Yeah, but like I’m just going to ask him to verify anyway’ you know? No hard feelings, you know how it is, and I’d be like no, I really don’t they don’t play Dota so how would they be able to verify if what I said is correct?”

They speak to some of the other barriers to them as well as women in esports.

“A barrier that exists is a lot of Tier 1 (to the top or highly skilled) teams won’t add women to their rosters because they see them as distractions or bad influences,” Linscott says.

On Sep. 19, 2023, it was revealed that a female Valorant player going by ‘meL’ had been rejected from playing on a Tier 1 team because a player was uncomfortable practicing with a woman.

The Esports and the gaming adjacent sphere, in general, have had many controversies pertaining to the abuse of women as well.

Such as the Smash Bros abuse scandal that took place from early July to late August 2020 where several top players in the community were accused of sexually abusing women who were, in some cases, minors.

Prominent figures such as Nairoby Quezada (Nairo) and Gonzalo Raúl Barrios Castro (Zer0) and many others were accused of this. Zer0 Is in the Guinness Book of World Records for being undefeated for 56 consecutive tournaments on Smash Bros for Wii U, Nario being the one to end his streak.

Linscott talks of other prominent scandals.

“It took up until 2020-2021 until the #Metoo movement really hit. Like Dota 2 and CSGO and I think it was also Overwatch that got affected by it. Other communities haven’t been but that doesn’t mean that the same type of stuff that was brought to light in Dota 2, for example with some of the casters having done some pretty horrific things, that doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist in other communities.”

This kind of behavior echoes the many scandals of traditional sports like football or rugby, despite the fact that Esports seems so different.

Linscott has even been discriminated against by higher-ups in the industry.

“I’ve had workplaces be unaccepting specifically when I came out as non-binary they were unaccepting of how I identified, which is like I had a boss who flat-out told me they wouldn’t use my pronouns that I had asked them to use.”

Steps have been taken to address these behaviours recently.

Amy Chen, an Esports journalist who has reported on several more inclusive stories regarding video games and Esports, gives her thoughts.

“On another higher level, perhaps Esports organizations can kind of create tournaments or communities or create content that sort of uplifts marginalized communities.”

A big first step into learning how to just talk to other people online.

Stan Usovicz

Initiatives such as Game Changers, which are headed by Riot Games (publisher and creators of League of Legends), are movements that are meant to create a safer space for women and other marginalized communities playing games.

Chen also highlights women in Esports who have made a name for themselves such as “Jessica” of Femme gaming or “Aerith”, a Famous Call of Duty Mobile player.

“I’ll say recently I chatted with a Call of Duty mobile player competitor and content creator. Her name is Aerith, yeah, it’s pretty amazing how she’s able to do what she loves and work with other people on it.”

Mafei talks of Humber’s Esports incentives to make the space safer for everyone.

“There’s companies like Femme Gaming, Black girl gamers, LCS game changers, and other ones that try to bring people with less voices and make them more prominent.”

There is still more that can be done through a sentiment shared by Egil.

“So I, in many instances, believe guidelines and policies are not in place. There needs to be, you know, more sanctions and consequences for those who engage in harassment and bullying. And also have support systems in place for victims.”

It’s often just a name change or an account change that can easily save someone who’s been banned from a certain event for a number of reasons according to Egil.

Bernard offers more advice as well.

“It’s about having systemic support. So, you have to bring in policies and practices are people that are like, from the top down looking at like, what are the broken foundations, and fixing those. He went on to list things like hiring and training as examples of things in Esports that should be fixed which would then improve things marginally in the long run,” Bernard says.

Stan Usovicz is the founder of Esports Scholar, and a member of the United States Esports Association, and he teaches his teams in regards to lessening toxicity in games.

“Working with your teammates is, I think, a big first step into learning how to just talk to other people online.”

Stan talks of his experiences with the teams he has taught as well.

“With our Esports program comes a lot of this idea of what does it mean to be a digital citizen? Those usernames in those lobbies are real people behind each of those. There’s a sense of community we try to establish.”

Kendryx gives this final word.

“So when we can fix these issues when we fix the systemic sexism that exists that goes WAY back to childhood when boys back in the day were taught that playing video games was fine and for girls and anyone who identified otherwise it’s not okay when we fix those issues when we fix the sexism that exists in the workplace when we fix all these other biases that exist then we don’t need those leagues but until we get to that point these leagues are critical for the success of women and gender nonconforming individuals.” Kendryx says.