From grassroots to organized competition

By: Eli Ridder

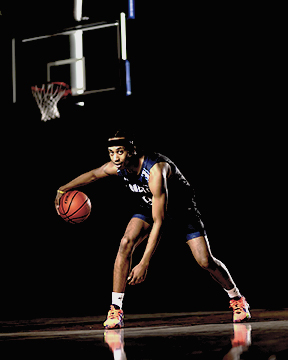

Jaheim Foster was attending high school in Florida, where there were better opportunities for his future in basketball, when the coronavirus pandemic sent the world into lockdown in March 2020. With restrictions easing over a year later, Foster is back in Canada playing basketball for the Lambton College varsity team. However, he almost didn’t make it to this point; it was playing a competitive basketball video game that kept Foster’s passion alive.

“I didn’t know if I even wanted to play basketball anymore,” the Lambton centre said. “If it wasn’t for video games and 2K in general, I would have lost interest in the sport, and probably would have went to school just to go to school. 2K has kept me locked in and [made me] realize that my purpose was to play basketball.”

Foster is not alone in a love for both physical and virtual sports. Fanshawe College varsity soccer player Michael Sumana turned to a game called Fifa when lockdowns brought the end of his high school and start of his college career to a screeching halt. Sumana turned to Fifa, a game built around every way to play soccer virtually, as a way to connect with his teammates.

With pandemic restrictions coming to an end for sporting events and athletes once again taking the field, Foster, Sumana and others like them are returning to the field. Though they may not have as much time to play esports now that in-person sports are back, that doesn’t mean the world of competitive video gaming at colleges is disappearing.

Esports is growing exponentially. In 2017, total esports revenue was $655 million, according to the Miller Thomson group. That number will hit or surpass $1.7 billion — fueled by sponsorships, ticket sales, merchandise and heightened awareness. Of course, for esports to exist, just like traditional sports, leagues need to exist in order for players to participate in, for there to be sales and for brands to thrive and bring in an audience. Over the past five years, there has been a move towards franchised leagues, a format familiar to sports such as hockey, football or baseball. A pioneer in this space has been the Call of Duty competitive community, perhaps the largest North American esport. With any major league comes the question of the amateur scene: how does one build the filler leagues that feed into the majors?

For years, traditional sports have relied on amateur leagues, often built up from high school and post-secondary institutions. Traditional associations such as the OCAA have existed to foster athletic talent, and the best-of-the-best will find their home in the major leagues. However, when it comes to esports, the students have built up the leagues themselves, without the support of the traditional sporting organizations and often on a volunteer basis.

The College Call of Duty League (CCL) is one of these leagues. It was started by two students who identified a need for some organization across colleges for the esport. Jacen Garris is one of these students. He views esports as an opportunity for less-established schools to get a chance at recognition, one of the reasons that Garris believes esports hasn’t been run by traditional associations which traditionally cater to the larger, more established sporting schools.

“A lot of these schools that have been winning a lot of events and doing really well, they are really small schools,” explained Garris. While a lot of the older, bigger institutions excel in traditional sports at the highest college levels in Canada and the United States, smaller campuses are able to find success in esports and get their name out. Another reason esports like Call of Duty, Overwatch, Valorant and others aren’t coalescing under organizations like the OCAA, Garris pointed out, could be due to how players earn money.

“Students who are competing for schools are also streamers, earning money from Twitch, playing in challengers or contenders and they’re playing in random local tournaments,” said Garris.

University of Ottawa in Virginia fields one of the best CCL teams in North America; it won the most recent season. Sergio Brack is the Ottawa team’s head coach, and said that, at least for Call of Duty, the college league is moving towards a more formal association, as the CCL was acquired by eFuse earlier this year. “You already start to see it becoming more organized,” Brack said.

As for the future, Brack said he sees the college route being the way for players to go pro instead of the many amatuer leagues. “There’s much more value at this point being in CCL and getting your education at the same time.”

Despite starting from a grassroots effort, the CCL, now under eFuse, is reaching new heights. Heading into its next season, the league is bringing in varsity standardization — a big step that brings at least COD esports to the same level as traditional sports associations. Varsity teams will differ from clubs and offer non-competitive benefits and an air of increased legitimacy to the schools that achieve the badge.

When post-secondary students first began structured sports, it took decades for the associations to form and for the leagues to be solidified. Garris pointed out that esports is going through the same process, but faster.

He said: “We’ve kind of done in five years with esports what football took 40 years to do.”