By: Cassandra McCalla

Black female athletes have always showcased their power in athletics but continue to face inequities and inequalities in their sport. For many decades, Black women in sports have always dealt with criticism and struggles. There has been great progress throughout the last couple of years but it still has not been enough to leave a positive, lasting, and permanent change.

Throughout history, black female student-athletes face double discrimination with their race and gender. They were not given the same opportunities that their male and white counterparts were given. They have faced stereotypes regarding the type of sports that Black women are expected to excel in such as Track and Field and Basketball. Through it all many Black student athletes endured and became trailblazers in their respective sports. Many have gone on to go to the grandest stage for an athlete, the Olympics, and some have become Olympic champions.

Former co-president of York University’s Black Indigenous Varsity Student Athlete Alliance (BIVSAA) and Track star Monique Simon-Tucker says the stigma with Track and Field athletes being mostly Black and the expectation that comes with it is wrong. “There are actually as many white athletes in track and field as there are Black athletes, but we have to remember that track and field isn’t just sprinting, throws and long distance events have a very diverse population,” Simon-Tucker said.

Black Indigenous Varsity Student Athlete Alliance (BIVSAA) is an organization that launched earlier this year that helps give a platform for Black and Indigenous student athletes. One of the things that Simon-Tucker is proud of with the alliance is that White coaches on York’s athletics teams were interested in hearing the experiences of student members of the BIVSAA.

“They all wanted to understand where we’re coming from, and how they can be the best allies they could be. I think that makes all the difference,” Simon-Tucker said.

“Those coaches continue to show this is a change that we need to make. We need to make scholarships for students, open our doors and understand that it’s such from a young age,” Simon-Tucker feels coaches wanting to learn and have these conversations helps.

Donnovan Bennett, a Sportsnet broadcaster and member of Ontario University Athletics Black, Biracial and Indigenous Task Force (BBI), was a guest speaker at one of Humber College’s North campus Journalism Agenda meeting on Nov. 22. He says inequities and inequalities do not start or end at post-secondary athletics in Canada. “The task force started when the racial reckoning really was a chance to have current, former BIPOC administrators, players, athletes and media members come together to talk about the experiences,” Bennett said.

Bennett says that the task force comprehends that there is something closer to equity and positive experience. “It can lead in showing other organizations that small steps can go a long way so that systemic issues that happen before or after might be eradicated over time. But it is not something that will happen overnight,” Bennett said.

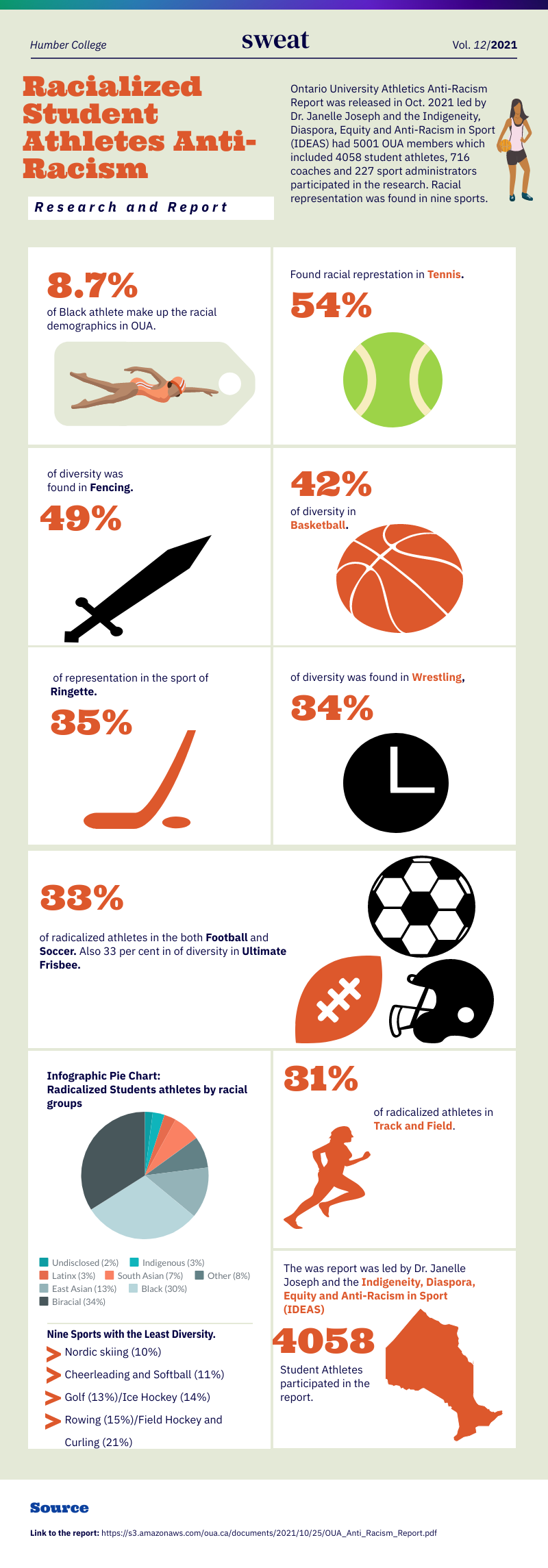

In the Ontario University Athletics Anti-Racism Report released in Oct. 2021 led by Dr. Janelle Joseph and the Indigeneity, Diaspora, Equity and Anti-Racism in Sport (IDEAS) had 5001 members which included 4058 student athletes, 716 coaches and 227 sport administrators participated in the research.

It reported only 8.7 per cent of Black athletes made up of the racial demographics where 71.3 per cent of white student athletes made up the overall average of racial demographics in the report. Racial representation in sports found that nine sports had better diversity which included tennis at 54 per cent athletes of colour, fencing at 49 per cent, basketball at 42 per cent, ringette at 35 per cent, wrestling at 34 per cent, track and field at 31 per cent and soccer, football, ultimate frisbee at 33 per cent.

That is true today with Black student athletes at Durham College as Megan Bent who is a first-year player on Durham’s women’s varsity rugby team said that although half of Durham’s women rugby team are Black women the team is still predominantly white.

Glory Ezeude, 22, and a third-year rugby player at Durham says that the lack of Black female players on the team is because of the lack of not having exposure to know where to apply. “In my first year, there were few Black girls that went on the team and they were interested in being on the team but were not aware of when to apply and try out,” Ezeude said.

Ezeude believes the sports management program that she is studying goes hand in hand with her being an athlete and playing rugby. “It does go hand in hand and some of the skills you don’t take in our running skills as we’re playing a sport whether it’s leadership, communication, teamwork we’re doing on the field should be reflected.” says Ezeude.

Onika Leveridge, a first-year Durham College student and a part of the Durham Lords Women’s Varsity Basketball team, said growing up she didn’t see a lot of girls who looked like her on the rugby team. “I remember being the one of the few Black girls in our entire league that was playing rugby,” Bent said.

“As I grew up I started seeing more come in, I do think even now Black women in rugby are only a small piece of the pie,” Bent said.

Rugby has been seen as a white-dominated sport because of the sport originating from England and being around since 1823. In recent years, Black women have shown up and helped make an impact.

One of the major inequities that Black female student-athletes face is financial costs as Bent said that many Black women’s athletes’ families are in circumstances where they can’t afford to help them. For Bent, growing up, her family could not afford to put her in an organization that can support her and cover her costs.

“I was only able to play at school and by the time I partnered with an organization that could support and cover me, I was able to play on a competitive rugby team,” said Bent.

“I grew up in Oswaha, and now they have these programs in Asad Durham where kids go to school half the time and train in their sport half the time but to get into these programs there is a huge financial cost.”

Bent said the key is to remove barriers early on because of the intersectionality of being Black and a woman of lower income circumstances and an international student and that will allow for better accessibility for their sport.

Black women dealing with the stigma of race and stereotypes with being in the sports, it feels as if they’re carrying the Black history struggle with them when they’re running on the track or running across the field kicking a soccer ball. Every time Black women student-athletes play their sport they must prove and work twice as hard to show their coaches, teammates and their opponents their worth and power in sports. They can’t let their opponents see them slip and sometimes that shouldn’t be the case.

Leverigde says the team that is predominantly Black was able to bond easier because they’re from the same area but it is not the same for other Black female student athletes in different regions. “A lot of Black people I know and people who are not of the caucasian race don’t feel comfortable in certain schools because they’re different,” Leveridge said.

For Leveridge, basketball means the world to her, but she says there are advantages and disadvantages in the sport. “Black women who are fit, tall or any type of athletic, you’re expected to play sports, that can be a good and bad thing,” said Leveridge

I use my God-given abilities and one of the disadvantages is also that there are a lot of expectations but also the expectations are low because they expect you to be nothing more than an athlete,” Leveridge said.

Leveridge says that Black Canadian women are not represented as much as their Canadian male counterparts, especially in basketball. The number has been rising in recent years. She also says that in Canada, Black female athletes don’t get the same publicized ads as white athletes do.

We see athletes making strides across the border in the U.S leading their voices in protest and marching with the Black Lives Matter movement especially with the shutdown of schools due to the COVID-19 pandemic. African-American basketball player and George Brown alumni Zae Sellers was one of them at the forefront during the last years protest’s over the George Floyd murder and many other gruelling events that happened.

Sellers says her experience as a African-American going to George Brown was a great one. “Being African-American and especially being an international student it was different not only just being Black but being an American, the cultural differences between the two countries and the school that I came from was different and awesome,” said Sellers.

For Sellers, going to George Brown, studying and being the Captain on the women’s Basketball team, she saw better diversity and welcoming compared to the U.S.

“I’m from Minneapolis, Minnesota. We have black people but in America overall, there’s such a division between Black, Asian, Latino,”

“I thought it was so cool going to school in Canada, because, yes, there are Black people, but they knew their ethnicity and they knew the country that they came from and they knew where their parents came from,” Sellers said

Black female student-athletes should be recognized and celebrated for their contribution in sports. Black female athletes are seeking greater and crucial change within varsity sport and in post-secondary schools that need to be implemented to have a better chance for lasting change for the next generation of Black female student-athletes.

Sellers hopes that Black female athletes continue to thrive and use their voice on social media or any platforms to showcase their achievements. “Excellence isn’t always seen, we might not always get the same coverage, but it’s important that Black women advocate and for our white counterparts that also advocate,

Just to know that it’s not a competition. It’s just simple recognition.”