By Nur Dogan

With the withdrawal of the U.S. troops from Afghanistan on Aug. 30, the 20-year-long war in the country deepened again. Women who had been improving themselves for years went back to 20 years ago, some of them are journalists. Those females not only lost their jobs but also had a close brush with death.

On 9/11, Al-Qaeda made four coordinated attempts and crashed the U.S. passenger jets into two New York skyscrapers at the Pentagon and in Pennsylvania. 2,977 people were killed. In the aftermath of the terrorist attack, the U.S. troops went into Afghanistan to hunt down Al-Qaeda and overthrow the Taliban. It was the longest war in American history.

However, in April 2021, U.S. President Joe Biden ordered the termination of the longest war to bring the American soldiers back home. The Afghan army and government were expected to fight the Taliban. But it was unexpected that Afghan former President Ashraf Ghani would flee his falling country and leave millions of his citizens alone in the middle of the fire.

The Taliban seized control of 33 provinces in just nine days, between Aug. 6 and Aug. 15. Next, the last city Panjshir was captured on Sept. 6, the Taliban announced.

Heather Barr, the associate director of women’s rights at Human Rights Watch and previously the Afghanistan researcher Human Rights Watch, lived in Afghanistan for about six and a half years. “Women journalists were one of the first sort of targets in terms of women’s rights that the Taliban went after,” she said. “Silencing Women Journalists was a high priority for them.”

So, they had to flee the country at once to stay alive.

Zainab Pirzad, the editor-in-chief of Rukhshana Media, which covers issues related to women in the domestic and international sector, and journalist at Etilaat-Roz daily newspaper, was among the evacuated female journalists.

Pirdaz talks about her experience when she arrived at the Kabul Airport, during evacuation day. “I just saw too many people and a dirty place. I did not know what happened,” Pirzad said.

On top of the chaos and ongoing violence surrounding the airport, Afghans were under the fatal threat of overhead electric wires above the gates. A crowd was expecting to step into the airport to be able to get on an airplane. Some civilians were begging American soldiers to let them into the airport.

Pirzad, who witnessed this turmoil, tells a conversation she had with someone who had been travelling for two to three days to reach the airport. “There was not a toilet.” Some were beaten by the Taliban while some saw elders and children die in front of them.

Pirzad witnessed this turmoil. “Someone said, ‘I was two or three days on the way —doors of the airport— to get in, and there was not a toilet,’” she said. “Other person said, ‘Taliban beat me,’ while another person said, ‘I saw how old people and children died.’”

Pirzad was able to leave Afghanistan on Aug. 22 with the help of foreign journalists, despite not having a visa from another country. “I have Special Immigrant Visas for Afghans, so I decided to go near the American Army,” Pirzad said.

Pirzad was able to migrate to the United States, but she still has growing concerns about the life of her family who she had to leave behind. “My dreams shattered, I even could not say goodbye to my dad because he was not at home, and I had to leave home soon,” Pirzad said.

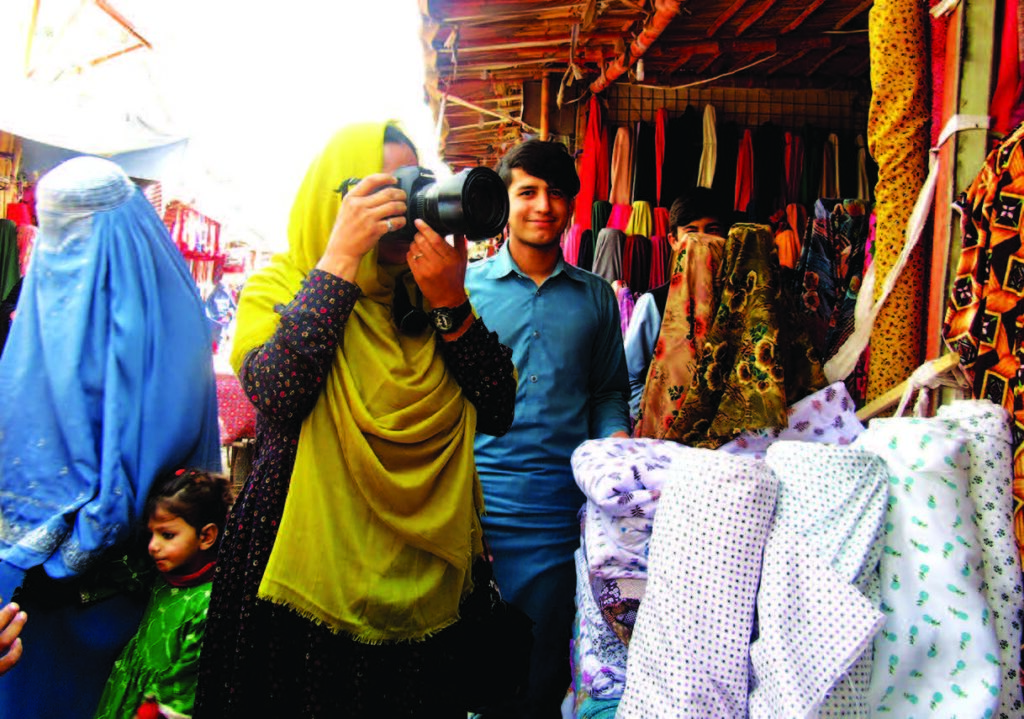

Women journalists are particularly vulnerable. “I left my country here in a really bad situation and untrusted way,” said Mariam Alimi, a freelance photojournalist who worked for many international organizations including the New York Times, Washington Post and the Wall Street Journal. She is another exiled women journalist who had to flee her homeland recently.

“I was feeling really bad. That’s why I had to leave my country, I had to leave all the things I did in the last 20 years,” Alimi said. “After this, I am not able to do it.”

Alimi was not only dedicated to shooting photographs for newspapers but also to training new photographers in Afghanistan. “I was the one who was travelling around the country in different provinces to teach boys and girls about photography,” she said. “But unfortunately, I was not able to travel alone around my country here anymore. So, all these things forced me to leave my country.”

Courtesy Mariam Alimi.

While the Taliban forces celebrated their victories shooting in the streets, women journalists found themselves in scary desperation and apprehension about their lives.

“I cannot explain my feelings, I am still shocked and can’t believe that I lost all my dreams,”

Pirzad said. “Taliban don’t allow women journalists to do their job. Of course, they will kill.”

When some women reporters were trying to make their way out of the country, others were sent home from their news offices by the Taliban with the order to “never come back.”

Marwa is a female journalist whose real name must be hidden because of her safety. She still lives in Afghanistan and used to work at traditional media.

“We did not know what the Taliban would do to us or whether we would be able to continue our work or not,” Marwa said. “It was an uncertain situation, I used to cry day and night with the thought of having to stay home for the rest of my life and not being able to work anymore.”

After a while, Marwa got back to work, but the working conditions were more different than before – potentially fatal. She said, “as long as we are able to continue raising our voice, it does not matter what they say to us.”

Despite all concerns, there was still some hope among the journalists as it was reported that the White House was negotiating with the Taliban to secure the sustainability of women’s rights. The Taliban`s spokesperson Zabihullah Mujahid, however, talked otherwise in his very first press conference on Aug. 17.

Mujahid said that Afghan women would have their rights, and the Taliban would respect them but “within the framework of Islamic law.” Women had to wear the all-enveloping hijab named burqa, and they would go out only when accompanied by a male relative.

“They talked about how men and women have equal rights, and they would respect all human rights, including the rights of women,” Barr said. “Then the next day they started firing women, journalists from the state media station from the National Radio and Television of Afghanistan (RTA).”

Marwa talks about an incident where she encountered a Taliban staring at her angrily. “Do not worry. I am going to make you dress modestly and behave like a true Muslim woman soon,” Marwa said.

Some male journalists also have been under the Taliban’s pressure as much as females. On Sept. 7, two male journalists covered the Afghan women’s protest who were seeking girls and their violated rights. The Taliban, however, detained the reporters, put them in separated cells, and beat both men with wires. After two days, they were released having their backs and faces severely injured.

During her interview on Oct. 11, Marwa told us that no female journalists have been hurt physically as the Taliban are trying to gain international recognition and support. “They don’t have the guts to hurt any female journalists for the time being,” Marwa said.

On the other hand, Interior Ministry spokesman Qari Sayed Khosti said that four women have been murdered in Mazar-i-Sharif, the northern city of Afghanistan on Nov. 6. One of those women that were shot dead was Frozan Safi, 29, a known women’s rights activist and university lecturer. So, the Taliban could not protect women as they promised.

“But I am more than sure that they will stop us from appearing on TV or working outside along with our male counterparts once they settle down fully,” Marwa said.

Now in Afghanistan, all women have been under the oppression of the Taliban. They banned girls from receiving education under the age of 10. Women have not been permitted to work outside their homes.

“The Taliban has a really oppressive approach to censoring and intimidating journalists and their work,” Barr said. “They face all of the same kinds of restrictions and fears that other Afghan women do about their freedom of movement and the risk of being harassed by Taliban members when they’re out and about, where they’re going, what they’re doing and what they’re wearing, and so on and so forth.”

Alimi said that in the past two decades, everyone had been investing in themselves and the country to enhance their education to have an identity. “So now leaving the country and being somewhere else, means that we really lost our identity, we lost our country, we lost everything that we can face in the last 20 years, just in a second,” she said.

Pirzad, who still has been actively working for Rukhshana Media, tries to be a voice to Afghan women. “In Afghanistan not just the journalists’ lives matter, all people are exposed to starvation and danger,” she said. “Girls cannot go to school and university. Women cannot go to offices.”

Barr said that Afghans have been negotiating with the Taliban, and some of those negotiations resulted in success. “The international community also has to be putting pressure on the Taliban over women’s rights in other ways, not ways that are essential to resolve in the humanitarian crisis, but political means things like recognition and so on that the Taliban does seem to want you to know, we saw how to tell them to be quite upset over being denied,” said Barr.

Barr said that the United Nations might be considered as a leverage to put pressure on the Taliban for massive violations including rights of women and the rights of media.”

Convergence reached out to two more women journalists currently residing in Afghanistan. One of them was psychologically overwhelmed by the fear of the Taliban. She said that she could not interview due to security reasons.

Another woman reporter was trying to flee the country because her life was imperiled under the Taliban’s rule. Therefore, the interview with her had to be cancelled. “I had to remove all my social media for a safe trip and reduce the threat,” she texted. “There is no facility right now, I do not have access to a PC, and rarely and difficulty I find access to the internet connection.”

Canada, the United States and countries in Europe warned the Taliban to ensure that Afghan women will not suffer new restrictions. Despite this, the Taliban have kept forcing women to live within the walls of their homes. Knowing this, many Afghan women journalists had to flee the country. Because there was no other way to maintain their professions.

Afghan women now hope to go back to the old days when they had been able to work as journalists, anchors, presenters and photographers. They would like to wear what colour or style they prefer. Afghan girls need to resume their education regardless of their ages.

As a result, they only demand the human rights that everyone inherently has across the world.