By Ross Lopes

In the world of news reporting, all beats tend to intersect at some point. Travel journalism intersects with environmental studies and cultural politics. Business journalism intersects with economics and technology studies. The same applies to entertainment journalism, which intersects with politics, social sciences and cultural issues.

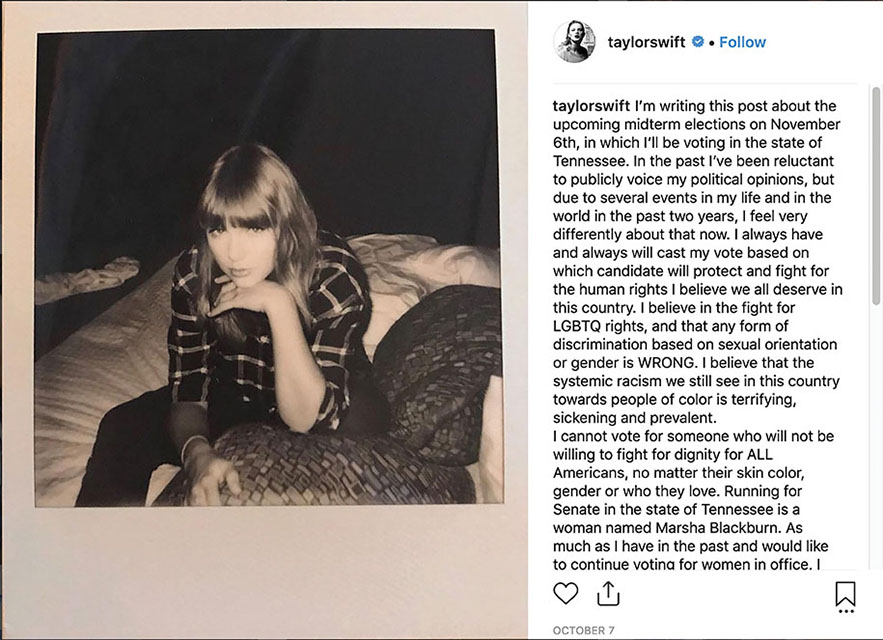

In October, Taylor Swift — who is known for keeping her political thoughts to herself — shared a statement on Instagram in support of the Democratic party.

USA Today reported on the statement. Maeve McDermott wrote, “it’s something she needed to do … Swift’s letter is a sign of positive growth — that beyond just stumping for women’s issues and LGBTQ rights, she’s now willing to do more to advance these causes by publicly supporting candidates who back these ideas, even if that means potentially upsetting fans with opposing political views.”

By the end of November, Swift topped the list of The Most Influential Women on Twitter for 2018.

This isn’t the first time celebrities have been seen crossing over into other areas of news, but it is important to know who is behind covering these stories.

In today’s media, the beat of entertainment or arts reporting seems to be undermined and criticized, and some journalists are even being referred to as “news personalities.” Yet, many industry insiders say entertainment journalism should be held to the same standard of ethical, honest, and factual reporting as any other beat-journalism.

“Storytelling, regardless of the topic, requires the same skill set,” Barbara Caines, the Journalism Program Coordinator at Seneca College, says. “Journalists need to be able to focus their story through a subject who is actively doing something of news value and they need to find out the motive behind the action.”

According to a report from the Ethics Advisory Committee of The Canadian Association of Journalism (CAJ), any journalistic piece should meet three major criteria. There’s purpose, which means evidence-based research and verification that helps to inform communities about topics they value. There’s also the element of creation; all journalists’ work must contain elements of original production. Finally, there’s method, meaning the piece should provide an accurate and fair description of facts or opinion

The CAJ’s definition of journalism states: “All three criteria must be met in order for an act to qualify as journalism. Failure to pass any one of these tests means that the act in question is not journalism, and only journalists will meet – or, at least, attempt to meet – all these criteria consistently, fully and deliberately.”

Caines says new journalists starting to learn about these fundamentals want to be taught the skills needed, such as being trained on live reporting and asking open-ended questions.

“I find young journalists are extremely grounded and know the hard work that’s ahead of them,” she says. “While we teach students to report on all subject matter, they are also encouraged to pursue their interests in entertainment — or other [journalism] — through a fair and balanced approach.”

Centennial College expects the same standards of reporting relating to imaging, video, analytics, data journalism, mobile technology, but goes a step further and teaches young journalists how to layer on different beats, Barry Waite, Chair of Communications, says.

“We believe very much in arts and entertainment as a discipline, but from the perspective of the [young journalists] we’re talking to, we’re seeing it more as a skill that someone with journalism training wants to add on to,” Waite says.

Centennial is developing a course specifically for Arts and Entertainment Journalism which will include courses that fit the CAJ’s standard of journalistic practice. Waite says it will also teach young journalists about developing their critical voice and help them learn about different types of photographic or video work, specifically relating to red carpet photography.

“I think it’s a legitimate profession that is going to continue [and have] a demand about it because people are always going to be interested in the whole gambit of arts and entertainment, whether it be very serious theatre down to sitcoms on TV,” he says.

Kamal Al-Solaylee, a Ryerson Journalism professor and former theatre critic for the Globe and Mail, says he fell into the craft of journalism and was seduced by the world of covering theatre, film and concerts.

Al-Solaylee says the heart and soul of writing arts content is criticism or reviewing, which means honing the skill of one’s critical voice. That’s something that’s very unique to arts journalism, he says.

“Some people might think that art’s a very soft subject, [that] it’s about meeting celebrities and chatting and going to the theatre all the time and actually, what I’ve noticed, is that it is such an under-recognized or unappreciated reporting,” he says.

One publication in particular that captivated the teenage audience using this form of arts journalism, and is starting to gain recognition, is Teen Vogue. The magazine, which was once known for being just a fashion magazine for teenage girls, has made the switch to covering cultural and political topics.

Sophie Gilbert, writing in Atlantic magazine, said, “In many ways, Teen Vogue is simply doing what a fashion magazine does best: observing trends and disseminating them. But it’s also giving young women valuable information about issues they care about, not to mention taking them — and their manifold interests — seriously.”

However, Al-Solaylee says some mainstream entertainment programs lack journalistic standards, such as Entertainment Tonight or E Canada.

“All that stuff is hardly journalism,” he says. “I would not call it journalism to begin with. It is basically celebrity PR and it’s just packaged pieces. They never ask any tough questions.”

Al-Solaylee taught an arts journalism course at Ryerson for three years. At one point in his lessons, he showed an interview between Ben Mulroney and Michael Bublé as an example of how not to do an interview. Al-Solaylee says the piece was a vacuous and vapid interview, and Bublé was asked nothing about his music.

“I think the better investment is investing in sort of arts journalists and people who ask hard questions. There are many of them at the Globe and Mail … who are very ethical and take the role of art very seriously,” Al-Solaylee says.

“What I try to do in my arts journalism course is that I need to make [students] believe what they are doing is important … I think the incentives or the other route is to invest in good training for journalists. Ask them to ask tough questions,” Al-Solaylee says.

And there are tough questions to ask, and important stories to be told.

In early 2018, the Canadian music scene was rocked by allegations of sexual assault against Hedley, a popular band that had just been nominated in four categories at the Juno awards.

The CBC’s Judy Trinh followed the story. Her reporting involved talking to a woman who alleged she’d been assaulted by the band’s singer, and verifying as much as possible. She spoke to lawyers about the ongoing court case, and even the band’s former drummer, who made accusations of his own.

The reporting obviously meant asking tough questions.

Back in 1981, Salem Alaton worked for the Globe and Mail. He had an extensive career there writing in the features department, which included arts, entertainment and sometimes travel. For the past 15 years Alaton has been a journalism professor at Humber College. He agrees with Al-Solaylee’s approach and says criticism is important for journalists.

“If there’s programming by journalists that features no critical projective at all, absolutely we can come in and deconstruct that and be critical of it,” Alaton says.

However, Alaton says journalism has always been beholden to commercial enterprises.

“If you go back three centuries, newspapers were more or less shipping news and royal pronouncements, but even that, of course, is also a form of PR,” he says. “But to say one thing is journalism and the other thing isn’t journalism misses the point.”

Alaton says there’s always been some version of “infotainment” in the news. News can be entertaining, but the work still has to be careful, accurate, serious and professionally produced.

“The arts are important; entertainment is one of those words that may be a little bit self-trivializing,” he says. “When it’s called entertainment, it doesn’t sound as if it has much nutrition in it. But it can, and it does.”

Alaton says that even big, hard news-focused outlets even sometimes focus on entertainment. He was a cultural correspondent in New York City in the late ’80s. The New York Times ended up deciding to put a picture of a Broadway show on its front page because Madonna was one of the actors in the play.

“Well, what’s the big deal?” Alaton asked. He says because Madonna had such a cultural pull, the New York Times — which he says is known as “being ostensibly the most serious and the most reserved publication on the continent” — had to feature it in their publication.

“That would never have happened if Madonna had not been part of that show,” he says.

Errol Nazareth, the host of Big City Small World on CBC Radio One, has been a music journalist for over 20 years, and a radio professor at Humber College. He says he doesn’t see this type of arts coverage anymore. He also says over the last ten years he’s noticed news outlets dedicating less space to traditional entertainment and music journalism.

In the ’90s, when Nazareth worked at the Toronto Sun, he says, “They had a full-time music writer that focused on all the big bands that came to town, had someone that … would write strictly about the independent music scene … and I was writing about hip-hop and world music.”

Nazareth says that there’s a different focus in entertainment journalism now.

“You don’t have that [anymore],” he says. “Now they’re trying to fill the pages of celebrity journalism, like what Kim Kardashian is doing and what’s Kanye doing. I don’t see much substance in there.”

Al-Solaylee says arts writing in Canada is still very much focused on American culture, and there just isn’t enough coverage of what Canadian artists are doing.

“There’s a lot of great stuff happening in Canadian film, in Canadian theatre, in Canadian music. And by that I don’t mean just the Ryan Reynoldses or the Justin Biebers … I just find that it’s such a shame that our — at least our mainstream media — pays so little attention to it,” he says.

Nazareth says one reason this is the case is the introduction of the internet and how people are now consuming their news. From what Nazareth has seen, publications are filling entertainment sections with fluff pieces like “Top 5 tweets from 5 different celebrities.” He says this shouldn’t discredit or undermine journalists, because journalists have simply been pushed out.

“Major papers feel like, ‘Hey, you know give the people what they want,’ and if people want more information on Kim Kardashian and Kanye West and Lady Gaga, then people just feed this stuff to them,” he says.

Nazareth says journalism has come to a stage where mainstream media is hurting, television is hurting, and everyone is hurting. He says publications are just trying to find “clicks” or views for their publications in order to gain advertising dollars. But, he says, not all hope is lost.

“I don’t think there’s any plan to undermine [journalism],” he says. “I think those of us who are in the trenches are still doing it and still using whatever few platforms we have to get the word out.”