By Emily Wilson

“We came upon a house where there was this young child inside, by themselves crying and basically I don’t know if the parents are dead.”

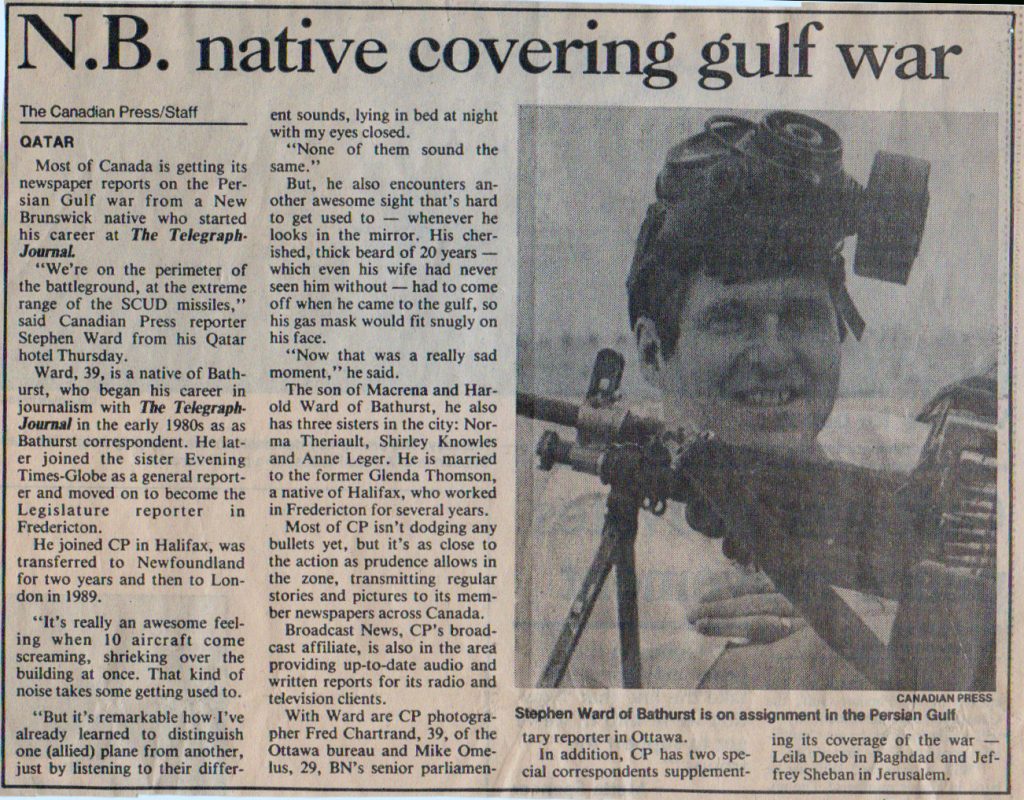

Stephen Ward was a war correspondent covering the unrest in Croatia in the 90s. He was in a small village after a combatant ruthlessly “ethnically cleansed” the area, leaving devastation behind.

“It was terribly heart wrenching,” Ward says.

The ethnic cleansing took place during The Bosnian War which occurred between 1992 and 1995. Yugoslavia was breaking apart and dissolving with many states becoming their own countries. A mass expulsion of Muslim Serbs took place during that time through violence and terror.

One of the photographers from Toronto also assigned to the story took photos of the terrible scene, stirring a debate on whether the photos should be used or not in the article Ward was writing. He says many argument points were used, but eventually a decision was made to publish. Factors included not identifying the people and location, as well as the responsibility to inform Canadians back home.

However, this situation could have had a much different outcome based on different choices made in the moment.

After retiring from being a reporter and newsroom manager, Stephen Ward became a media ethicist. Ward is a founding chair of the Ethics Committee at the Canadian Association of Journalists (CAJ) and a co-author of its two codes of ethics.

He says debates like the one in Croatia happen every day in journalism when sensitive topics are reported on. Standards change all throughout the world with different ethical standpoints and morals. But an unofficial code surrounds the sensitive content discussed in the news.

Jesse Winter is a freelance visual journalist and writer based in Vancouver. He believes much of the debate around ethics in terms of photojournalism comes down to consent and the ‘do no harm’ approach. “We saw a lot of [it] during the Black Lives Matter protests this summer, with questions about whether it’s ethical to show protesters faces, without their consent, with their consent, all of that kind of stuff,” he says.

Campers settle in for the first night at a new homeless encampment on Vancouver’s waterfront after the one at Oppenheimer Park was shut down by the City of Vancouver. (Jesse Winter)

Workers from Unite Here Local 40 walked a picket line over their lunch hour outside the Hyatt Regency Hotel in downtown Vancouver on Tuesday. (Jesse Winter)

Supporters of the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs march through east Vancouver carrying illuminated signs reading “No CGL & TMX Pipelines!”. RCMP raids of Wet’suwet’en land defender camps opposing a natural gas pipeline near Houston, B.C. sparked weeks of nationwide protests that hobbled Canada’s economy. (Jesse Winter)

Being a reporter with interest in social justice, he often finds himself with opportunities to allow for a double interview, an approach he wishes more journalists would adopt. He steps away from his own interests and provides his sources the opportunity to interview him and build a rapport. “I’ll say, ‘hey, this is the story I’m working on. This is what I’d like to talk to you about. But before we do that, do you have any questions for me’” he says on how he approaches subjects.

Patricia Elliott, a journalism professor at the University of Regina and investigative journalist, says there is a sense of vulnerability in informed consent, especially in her investigations. She says going that extra mile offers comfort levels and protections for people.

“You really have to go carefully to ensure that people don’t put themselves in a situation where, you know, there can be some unexpected negative repercussions,” she says.

Ethics itself is based on standards of right and wrong that often determine how humans behave. Usually this is based on rights, fairness, benefits and personal morals. In journalism these standards take a front row seat to ensure reporters uphold morals during situations in the news of death, sexual violence or reporting on certain vulnerable communities. Especially when sensitive information is shared.

Problems arise when journalists veer or falter from their publication’s code of ethics. News organizations would have the biggest penalties when a journalist breaches its ethics, but it still only comprises job loss or ruined reputation. It all depends on the severity, Ward says.

The past few years have seen a number of events with questionable decisions. Some of these events can range from writers being non-partisan with their opinions, promoting political views, endorsing candidates and making offensive comments over social media. With the new world of online journalism, personal stances became acceptable. “If you look at the CAJ code, the word objectivity does not appear, and that was a signal that [values] were changing,” Ward says.

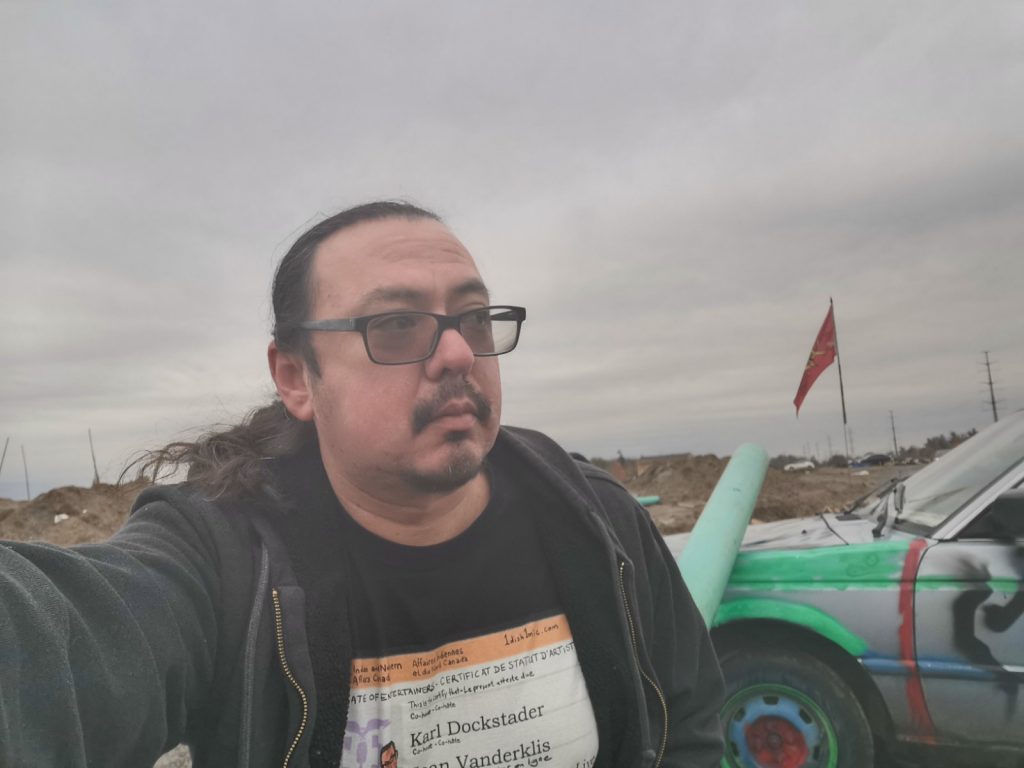

Karl Dockstader, an Indigenous reporter from the Oneida Bear Clan in the Six Nations, says that opinions, though valid in certain types of writing, should come with an ‘accountability standard’.

Karl Dockstader, an Indigenous reporter from the Oneida Bear Clan in the Six Nations, hosts One Dish One Mic, a talk radio show on NewsTalk 610 CKTB Niagara. (Courtesy Karl Dockstader)

The lack of accountability can sometimes be seen in right-leaning publications, with columnists and editorial writers, he says. An example is the late Christie Blatchford who wrote for a number of Toronto-based publications, the longest being The National Post.

He says writers will often present an argument that ends up not having a foundation of truth in the future and results in no responsibility to do the equivalent of a retraction when proven false.

“That’s the whole problem with the way that the editorial structure is written right now,” Dockstader says.

He says “supposedly objective journalism” has clear standards if stories are proven to be biased but editorialists have the ability to write freely as long as “the word opinion is at the top, and then I can do whatever I need to do,” he says. “I think there should still be some accountability factor to it.”

Over her career, critics said Blatchford’s writing took a one-sided approach without the view of communities outside of her own and her publication’s world.

Elliott says pure objectivity is an abuse of the journalism platform because fairness is different. “You can have a point of view, but you still need to be fair, in how you present the information and how much you are willing to talk to and listen to all sides of an argument,” she says.

Dockstader says the issue is not just about white supremacy. Male supremacy, misogyny, heteronormative practices and ableism all play a part in newsrooms to get the kinds of stories she would have written.

“I think that executives of newsrooms should actually disclose what the makeup of their leadership is in regards to those norms,” he says. “That’s going to give me an idea of what their standard of normal is.”

There is a responsibility of journalists to minimize harm and a “responsibility to try get it right,” Ward says.

The evolution of journalism accounts in large part for the evolution of ethics and standards. Journalism has evolved into a profession that a lot of people can do and from anywhere in the world. The introduction of the internet and social media allowed journalism to pull away from the mainstream. Ward says people started to become attracted to journalists writing their own opinions.

“And so, the stodgy standard bearers of the traditional neutrality were being pushed to write in a more personal perspective,” he says.

But this really cannot happen without a stronger set of enforced guidelines. The CAJ’s current standards were written in 2011 and so much has changed since then.

Winter says ethics is due for a refresher. “I think we’re in a time of pretty significant flux right now, in terms of how the industry as a whole thinks about issues of ethics, and morality, and consent,” he says.

He suggests that the journalism profession, which by the way was only 50 per cent trusted in the U.S. in 2018, according to a Statista survey from Forbes, might benefit from a professional school.

“In the same way that other professions would have, disciplinary processes, like doctors can be disciplined by the College of Physicians if they breach ethical guidelines,” Winter says. But it comes with its own problems. “That’s a really thorny issue, because very quickly, you get into this question of, who gets to decide who is a journalist and who isn’t?”

Elliott says the industry is widely self-regulated and because of this, an independent body could be used to handle breaches in a more decisive way. “I’d be in favour of seeing more arms or bodies to handle complaints and breaches than what we haven’t counted for right now,” she says.

Freedom of speech is not freedom of consequences. And journalists who stray should be more accountable, assuming they know the limit.