A Threat to Canadian Journalism

By Angelina Kochatovska

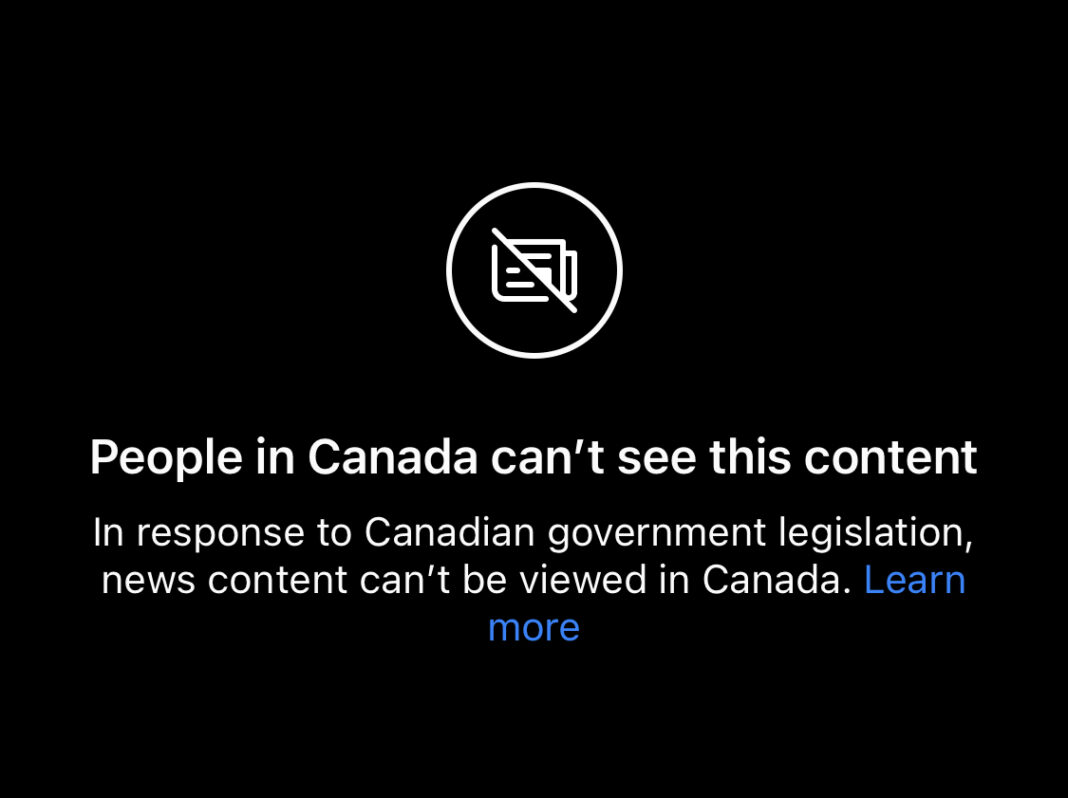

“People in Canada will no longer be able to view or share news content on Facebook and Instagram,” says Meta in their official statement after starting to block the links to Canadian organizations’s news content on June 1, 2023, in response to the government’s news act.

Carmi Levy, a journalist and tech analyst, says that the government opened a “Pandora’s Box” by implementing Bill C-18 and causing other issues to threaten the Canadian media industry.

“Canadian consumers are stuck in the crosshairs of the government’s intent to level the playing field and force major technology platforms to pay their fair share. And now the companies are essentially threatening to take their ball and go home,” Levy says. “That is a very dire position for Canada’s media landscape to be in as they look for legitimate sources of information in the digital space. It means that Canadians won’t have as easy or direct access to the critical content, they need to know what’s going on and form their appropriate opinions, and it makes it much easier for them to be misinformed.”

The problem with Bill C-18 is Bill C-18.

Michael Geist

The Online News Act, also known as Bill C-18, became a stumbling block between the federal government and big digital platforms. The legislation was introduced and passed by the House of Commons in Ottawa a year ago but became one of the most discussed topics in the media industry after receiving the Royal Assent (the approval by the Sovereign of a bill that becomes an act of Parliament and part of the law in Canada) on June 22, 2023.

According to the federal government, the bill was introduced for only one purpose – to support news businesses by securing fair compensation when their media content is made available by dominant digital platforms such as Meta and Google. However, the legislature faced a backlash from the companies that decided to remove Canadian news in response.

Some experts weren’t surprised by the reaction of digital platforms.

As Michael Geist, the Canada Research Chair in Internet and E-Commerce Law at the University of Ottawa, says, “The problem with Bill C-18 is Bill C-18.”

Geist says that the reaction of digital giants is understandable because Meta is not the one that publishes the news content.

“In the case of publishing, newsrooms deserve compensation,” he says. “But Meta doesn’t post news, publishers do. And the fact that it [Bill C-18] sought to suggest that links were something that merited compensation is a deeply troubling principle.”

Some people might think that Canada is the first country to ask digital platforms to compensate news organizations. However, the precedent took place in Australia in 2021.

That is a very dire position for Canada’s media landscape.

Carmi Levy

The Australian government presented the policy initiative called the News Media and Digital Platforms Mandatory Bargaining Code to force digital companies to pay Australian media outlets for using their content on the sites. After that, Meta protested the law by blocking news on its platforms across Australia.

Levy, who covered the Australian case, says Meta and Google were “dissatisfied” with the document.

“They fought it tooth and nail, including threatening to go dark in Australia and no longer carry content from the country’s media producers,” he says. “And only at the absolute last minute, the Australian government agreed to make some fairly significant changes to the law to, basically, water it down and limit the financial exposure of the technology platforms.”

As a result, Facebook and Google lifted the restrictions, and the law was passed with modifications.

One of the reasons why Canada couldn’t follow the same Australian success is the difference between the media markets.

“I think Australia is a more significant market than Canada. This is the home of Rupert Murdoch and News Corp. There’s more money,” says Brett Caraway, a professor of Digital Media at the University of Toronto.

Moreover, the overall news market doesn’t have a significant value for digital companies.

“The news has never been so important to Meta or Google because that’s a very small market – a small slice. If we’re talking about Canadian journalism, it’s a little teeny tiny slice,” says Brett Caraway, a professor of Digital Media at the University of Toronto.

“I think we need to look at Instagram, Facebook, and Google uniquely. Having Canadian source media content go dark on Instagram was more of an inconvenience than anything else because let’s face it – we all use Instagram for pretty pictures and videos. We don’t use Instagram to discover or surface media content. No one goes to Instagram for news. I say that as a technologist,” Levy explained.

Google warned that Canadian news content will go dark in December 2023 and in the eleventh hour the government of Canada managed to make a deal with Google on November 29.

“The Government agreed to discuss the possibility of addressing some of the most critical issues, which we welcomed,” says Kent Walker, Google’s president of Global Affairs, in the official statement. “In that discussion, we asked for clarity on financial expectations platforms face for simply linking to news, as well as a specific, viable path towards exemption based on our programs to support news and our commercial agreements with publishers.”

One of the biggest technical platforms agreed to pay $100 million a year to Canadian news organizations based on the number of full-time journalists they employ. Also, Google will continue to make training and other resources available to Canadian news organizations on top of its annual cash injection.

If we’re talking about Canadian journalism, it’s a teeny tiny slice.

Brett Caraway

However, Geist thinks that many Canadian media outlets will end up with less funding than they had before.

“There’s some new money but it’s pretty small for the scope of the sector,” he says. “Google was already spending millions of dollars on deals with some of the large publishers such as the Toronto Star and The Globe and Mail and those deals will disappear. They’re left to get a share of a relatively small pot considering how widely it will be distributed.”

At press time, Meta didn’t comment on the deal yet continuing to erase Canadian content on its platforms. Convergence Magazine attempted to reach out to Meta for comment but received no response.

“Meta has now blocked news links for months in Canada indicating that there haven’t been any negative effects from an economic perspective. So it doesn’t seem likely that they’d be willing to pay very much for news links,” Geist says.

He also says that Bill C-18 doesn’t exist anymore in the form it had been introduced before.

“In striking the deal with Google, one of the most notable aspects is that the government has largely tossed aside all the core principles that were critical in the law itself,” he says. “The law was supposed to be about the government simply facilitating negotiations between platforms and media companies with no direct involvement. Instead, what we’ve left with is the government literally negotiating the actual amount to be paid and even intervening in how that money will be allocated. So it’s a completely different law.”

Carey French, a professor of media law at Humber College, thinks that there is still time and place to sit down at the negotiating table and address the issues caused by Bill C-18.

“It seems to me it’s something that could be solved by sitting down and

having a reasonable discussion without actually giving up the farm.”

Some experts says they are surprised by Canadians’ unawareness of the potential threat Bill C-18 may cause to the access to verified information.

Last year, Abacus Data commissioned by Google Canada, surveyed to find out the extent of Canadians’ awareness of Bill C-18. They found out that 33% of respondents are “somewhat familiar” with the bill and only 8% of Canadian adults are “very familiar.”

As for the legislation’s requirements, only 21% of Canadians believe that a social media platform should be required to pay the news organization for sharing a link.

“Most ordinary citizens find anything to do with tech legislation to be as boring as watching water evaporate,” Levy says. “They don’t understand how that really colours their lives and they don’t want to take the time to learn. As a result, it opens the door for a lot of really bad policy decisions because the population has shown they don’t care.”

One of the recent examples that shows the growth of the ongoing disinformation due to the elimination of Canadian news content was The Beaverton, the popular news satire website, which was briefly put under Meta’s restrictions due to an automated classification based on metadata. A few days later, the situation was resolved after consultations with the site’s founder. However, that raises another concern – the blockage of news could result in the growth of fake news content among Canadian consumers.

“The absence of these legitimate sources will only create a vacuum into which more misinformation would flow,” Levy says. “It would fundamentally change how our entire audience consumes content and finds news articles and interacts with them.”

Despite reaching the agreement, Google still shares its concerns over the legislature that will be in effect by December 19, 2023.

“We hope that the Government will be able to outline a viable path forward. Otherwise, we remain concerned that Bill C-18 will make it harder for Canadians to find news online, make it harder for journalists to reach their audiences, and reduce valuable free web traffic to Canadian publishers.”

Levy added that Canadians should pay more attention to the changes in the media space.

“The entire health of the Canadian media ecosystem hinges on this. And they’re [Canadians] only going to realize it after it’s too late after they’ve lost access to the voices that used to inform them. And then, they will shrug their shoulders and won’t even realize that they could have been part of the solution that wasn’t,” Levy says.